By Benjamin Niedzielski on December 12, 2018

If you have done work in the Humanities, you have likely come across the concept of “close reading” — the careful, detailed examination and interpretation of a short passage of text. The understanding gained is precise and, when done well, shows important information about the text as a whole.

Close reading, however, can and should be supplemented by an understanding of the overall themes of the text. What are the key terms used? How much more space is devoted to one topic than to another? These questions aren’t answered by close reading alone. In fact, when considering a very large text or group of texts, these questions can be difficult and time-consuming to answer.

Text visualization tools can be helpful in this instance. Given one or more electronic texts, a tool like Voyant can help to answer these questions, supplementing the insight gained from close reading. Voyant can be used to create visualizations such as a “word cloud”, where words that occur more frequently in a body of text will appear larger in the word cloud.

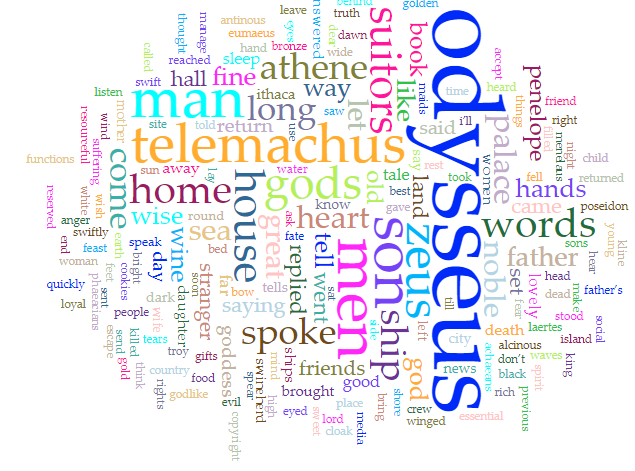

Below is a word cloud generated for A. S. Kline’s translation of Homer’s Odyssey showing the 195 most frequent words. Voyant automatically removes words like “a”, “the”, and “is”, leaving only more meaningful terms. You can also change which words Voyant removes, if you want.

If you are familiar with the Odyssey, many of the high frequency words, which show in larger text in this word cloud, will not come as a surprise. The main characters are particularly prominent – Odysseus, his son Telemachus, his wife Penelope, and the gods Zeus and Athene (Athena). Voyant helps us to see that the name “Odysseus” occurs with the highest frequency by far of all the characters. We can also see some of the major themes of the work, such as “house” and “home”, which Odysseus wants to return to from his long voyage, and which Telemachus wants to protect from Penelope’s suitors (another significant word in the visualization). Other common words are parts of phrases repeated throughout the work – “spoke” and “words” are common because the narrator often introduces dialogue by using a phrase such as “he spoke with winged words”.

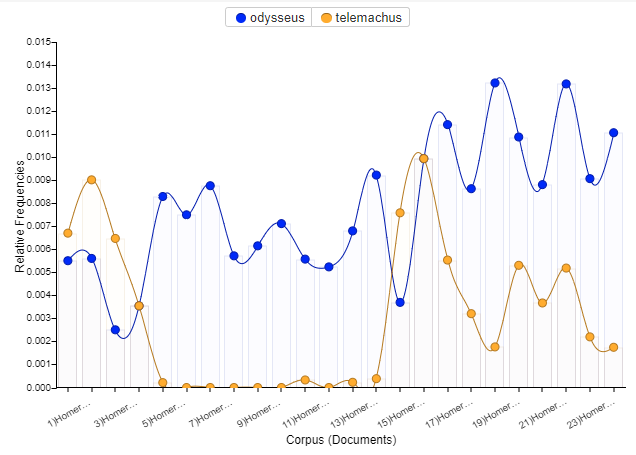

Word clouds, then, are useful for “previewing” a text for important characters, themes, and phrases. This information is no replacement for close reading, especially since there is no context, but it can add to an analysis. Voyant supplements the word clouds it generates with the frequency of common phrases and the distribution of words throughout a body of text. We can see from the below Voyant graph that Odysseus is prominent throughout the entire text, but his son Telemachus is mostly absent from books 5 through 14.

Still, if we look closely, we can see some issues with the word cloud. “Man” and “men” appear separately despite representing the same idea; if they were combined, they would be nearly as large in the word cloud as Odysseus himself. These problems become more prominent when we try to use Voyant for texts in other languages.

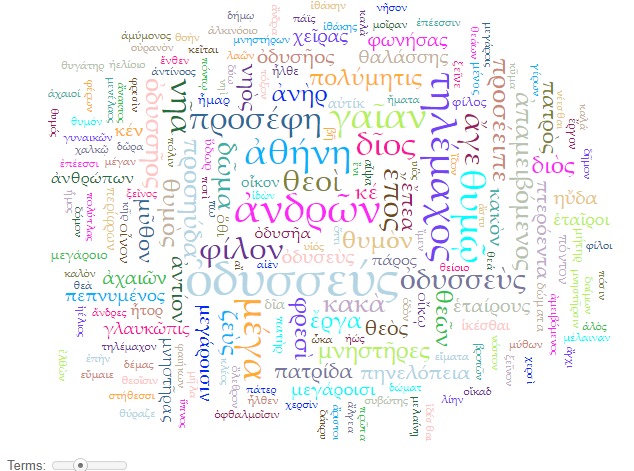

Voyant does offer support for a wide variety of languages, not just English. Since the Odyssey was originally written in Ancient Greek, we can examine the word cloud created from the original text.

Whether or not we can read the Greek words, we can see immediately that no single word is nearly as large as Odysseus was in the English cloud. What’s the reason for this? Unlike English, Ancient Greek is a language where the endings of nouns change based on how they are used in a sentence. A good comparison in English is how “he”, “him”, and “his” are all used in different ways — you wouldn’t say “Him went to the store”. So, while the word “Odysseus” can be used in English no matter where in the sentence it goes, Greek has to use different forms, such as ὀδυσσεύς (subject form) and ὀδυσσῆος (possessive form). As is true with “man” and “men” in English, Voyant separates all of these forms. In the word cloud of the original, Voyant downplays significantly how important Odysseus is to the text, since he is split into numerous word forms in the word cloud. The same thing happens in other languages that use endings in this way, such as Russian, Latin, or even Old English.

Finally, what about languages that do not put spaces between words, such as Japanese and Chinese? Here, Voyant is unsuccessful. It makes an effort to separate words, but there seems to be no consistent pattern in how it tries to do so, making the results meaningless. I attempted to make a word cloud from 9 short stories by Unno Juza, an early 20th century Japanese science fiction writer. In one of these stories, the two-character word “暑さ” (‘heat’ or ‘hotness’), occurs in consecutive phrases. The first time, Voyant separated this word into two separate words. The second time, Voyant combined the entire phrase into a single word. As a result, the word count for “暑さ”was zero, not the two it should have been. This and similar problems with other words made the generated cloud not useful for my analysis of a Japanese text.

Voyant’s word clouds can be very helpful for getting a sense of large amounts of text as a supplement to close reading. Beware, though, that for languages that change the endings of words to show how they’re used in a sentence, or for those that do not use spaces to separate words, Voyant may not be as useful as we’d like.

Main photo and screenshots provided by the author.

Resources:

- Homer’s Odyssey – edited by A.T. Murray (http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0135%3Abook%3D1%3Acard%3D1)

- Homer’s Odyssey – translation by A.S. Klein (https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Greek/Odhome.php)

- Jisho.org – 暑さ (atsusa) (https://jisho.org/search/%E6%9A%91%E3%81%95)

- 三十年後の世界 (Sanjū-nen Go no Sekai) – written by Unno Juza (https://www.aozora.gr.jp/cards/000160/files/2617_23917.html)

- Voyant (https://voyant-tools.org/)

- Wikipedia – Unno Juza (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unno_Juza)